VENICE – While many attend the Venice Biennale to savour the perspective of artists looking at the reflection of our collective reality, others seek an even deeper messaging relating to the dialogue between cultures, nations and civilizations. The stories are not just about the immediate and the contemporary – there are also backstories, untold stories and histories, such as The Great Game which, as curator Marco Meneguzzo says, was a play for supremacy between the Russian and British empires that affected a large geography, encompassing India to Iraq, Central Asian Republics to Afghanistan and the Persian Gulf. The Iran Pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year – all 2,000 square metres of it – attempts to redefine The Great Game into a New Great Game, “tearing down the ceiling of the universe to create a new design,” to use a quote from the Faiznia brothers, who valiantly made this initiative happen with the support of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art and its leader Mr. Molla Norouzi.

It is about new beginnings and well-known tales, fresh creativity and revisited political thoughts. Indian artist Hema Upadhyay treats the familiar theme of birds inside a display cabinet, not far from another enclosed cupboard of jars confining images of Iranian people inside it, by Babak Kazemi. Ghasem Hajizadeh’s witty deconstruction of cultural imagery sits informatively near socially expressive compositions by the popular Mohebali. We see familiar canvasses by Mohammad Ehsai alongside new calligraphic works by Pouran Jinchi, back-illuminated quotes from Mahmoud Bakhshi next to his iconic fragmented map of Iran. The truth is that there are so many talented Iranian artists, one sympathizes with the challenge of the selection process.

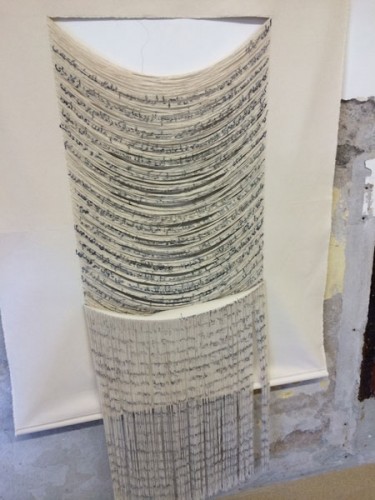

A piece by Nazgol Ansarinia at the Venice Biennale’s Iran Pavilion

A piece by Nazgol Ansarinia at the Venice Biennale’s Iran Pavilion

Superb works by Nazgol Ansarinia and Reza Aramesh vie with strong statements by Mehdi Farhadian about the senate house and an abandoned parliament; Pakistani Imran Qureshi shows a canvas which wavers between the abstract and the political, while Mulji’s camel sculpture sitting at the very entrance to the shows leaves us in no doubt about the territory we are entering. Walid Siti’s extraordinary refined sculpture of a fictional barbed-wire map balances beautifully against the elegant proportions of a magnificent geometrically inspired sculpture by Sahand Hesamiyan. But, conspicuous by absence were a late-arrival Tanavoli sculpture still stuck in customs, and Monir Farman-Farmaian withheld due to concerns for safe transit. Unpacking and installation were still ongoing at the opening, but none of it deterred my enjoyment of that exceptional installation by the late Farideh Lashai – her Rabbit in Wonderland depicting the illusiveness of political independence. For those with an interest in the Iranian art scene, this is a must-see.