What to See in New York Art Galleries This Week

By Martha Schwendener, Jason Farago, and Will Heinrich

Jan. 24, 2018

Jacques Monory

Through Feb. 23. Richard Taittinger Gallery, 154 Ludlow Street, Manhattan; 212-634-7154, richardtaittinger.com.

Jacques Monory’s “Béatrice et Juliette n°1” (1972) at Richard Taittinger Gallery.

Credit2018 Jacques Monory/Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Richard Taittinger

Jacques Monory, well known as a painter and filmmaker in his native France, is having his first solo show in the United States at the age of 93. Fittingly, the exhibition at Richard Taittinger surveys Mr. Monory’s paintings from the past four decades, highlighting his engagement with photography, popular culture and the monochrome.

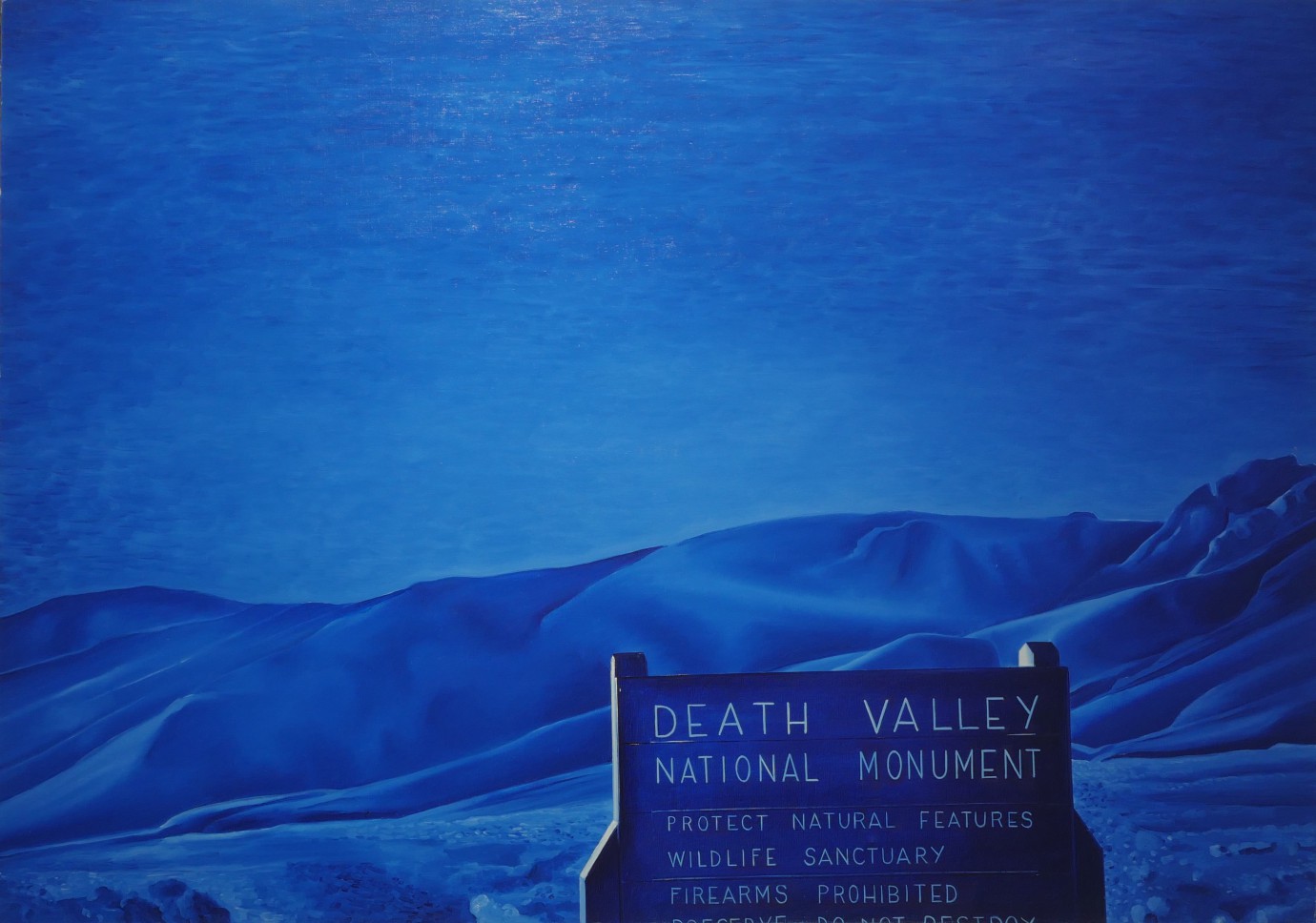

“Death Valley n° 4” (1975), by Mr. Monory, who is having his first solo show in this country at the age of 93.

Credit2018 Jacques Monory/Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Richard Taittinger

Mr. Monory was part of a ’60s movement called Narrative Figuration that struggled to distinguish itself from both American Pop Art and earlier French artists. Yet you can see these influences (that of movies, in particular) in Mr. Monory’s Pop subject matter and signature blue palette, which harks back to monochrome specialists like Yves Klein, famous for his International Klein Blue.

The importance of photography is evident in paintings like “Béatrice et Juliette n°1” (1972), which looks like a hipper (and bluer) version of a Gerhard Richter canvas, with its right panel smeared into indistinguishable blurriness. “Death Valley n°4” (1975) reflects an interest in American subjects (especially film noir), but also the death drive of planned-obsolescence consumer culture.

Mr. Monory’s canvases can be easily compared to the work of ’80s American postmodern painters like David Salle, Jack Goldstein, Troy Brauntuch and Eric Fischl, but he has a soft spot for older figurative artists, too, like Edward Hopper. “Spéciale n°54 Hommage à Hopper” (2007) features a house with a nearby road sign for the Hopper Center — although no such institution exists, except in this painting, which functions, as does most of Mr. Monory’s work, like a movie screen where fantastical drama and action are routinely played out.

MARTHA SCHWENDENER